Interview of Olga V. Smirnova to American economist John Reid

_

On June 5, 2020, an interview was conducted by American economist John Reid and professor of the Center for Forest Ecology and Productivity of the Russian Academy of Sciences Smirnova Olga Vsevolodovna. John Reid is writing the book about the world’s forests, which he hopes to draw public attention to the current situation in the world – catastrophically fast reduction of vast forest areas and destruction of forest ecosystems. John Reid personally visited the rainforests of Africa and South America. John Reid asked the Russian scientist about the situation with the harvested forests of Northern Eurasia.

_

The main questions and answers from an interview with Olga Vsevolodovna and John Reid:

How would you describe to an ordinary person the differences in how an old-forest and a post-logging forest function?

The simplest sign of a natural forest, that is, a forest that has existed over the course of many generations of trees of different species without felling, fires and other influences. There are in the population of each species of tree of individuals of all stages of development: from seedlings (plants that have just appeared from seeds) to large trees dying of old age, whose age is several hundred years. The structure of such a forest is beautifully described by A.S. Watt, 1925 and is called «gap-mosaic» – mosaic of renewal windows. This is a complex combination of glades with grasses, shoots and young trees; with trunks of dead trees filled with life: these are jointly existing soil animals, mushrooms, mosses, microorganisms and other creatures.

_

How is the fauna and fungal life different in an old-growth forest compared to one that has been logged? What’s the sensation you have when you walk into a healthy, old forest? What are you looking for?

Closest to natural forests are those that A.S. Watt described in the gap-mosaic. Intact natural forests are absent both in Russia and on most of the Earth, since they are completely devoid of the main inhabitants of natural landscapes – giant phytophages of the mammoth complex and a significant part of the prehistoric Earth Biota as a whole. Unfortunately, the big achievements of paleontology over the past centuries have not yet been recognized by the World Community, therefore, fragments of preserved modern Nature are considered as the standard of Nature, the incompleteness of which is clearly manifested in the process of paleoreconstruction.

_

Given that prehuman Siberia was a forest-grassland-wetland mosaic, do you think there is “too much” forest there now? Is it possible to prescribe how the ecosystem should be?

I do not think that we know what the territory of Siberia was in the pre-anthropogenic period. Some of its resemblance was recreated in S. Pleistocene Park by Zimov. Prehistoric Nature can be reconstructed (at the model level) according to the huge paleodata accumulated to our day. The problem of preserving the fragments of Nature is that we accepted the Earth, which was severely disfigured by man at the end of the Pleistocene-Holocene, as a natural (pre-anthropogenic) formation, and so far we are only mastering the main features of its pre-anthropogenic organization … The biggest misfortune of mankind is that it has not yet realized how much Nature needs help to preserve the remaining fragments of the past and how to do this without causing new disasters.

_

Why do larches predominate in many Russian boreal regions but not in North America?

Larch does not prevail in the forests of Russia. In the first place among coniferous trees is spruce (different species) and, less commonly, fir. As for the fate of larch in North America, as well as about other species, one should consult with experienced paleontologists and specialists in the history of nature management. So, for example, while inspecting forests in Northern Yamal (Russia), we accidentally found that local residents prefer larch to other species when preparing poles for their plague and almost completely destroyed it, roaming around Yamal and destroying trees at each new parking lot.

_

What do you still want to learn about forests?

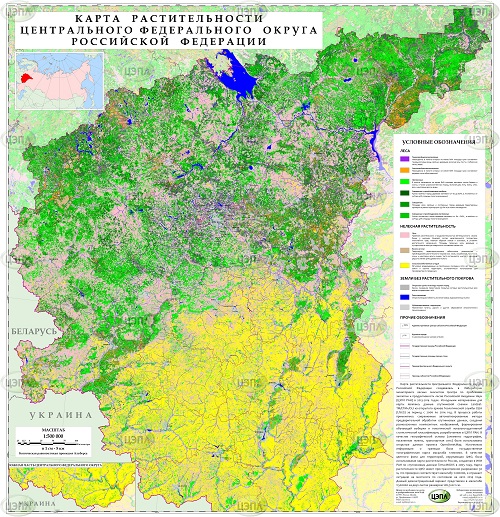

My colleagues and I published the book European Russian Forest / Their Current State and Features of Their History (https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789402411713) and we plan to develop programs to restore the composition and structure of the prehistoric forests of Russia based on the paleo data accumulated by the international community and try to implement them on model training grounds.

_

What have you done to make young people care about forests?

I brought up post-graduate students, some from them became doctors of science and further advance our common achievements in forest ecology. I collaborated with the Russian branch of Greenpeace and WWF. Now I am preparing with my colleague’s presentations on the topic: Ecology for everyone, where we explain how the prehistoric Biota was organized by the example of the territory of Northern Eurasia, what are the most acute problems and tasks. We are advocate this knowledge in our Russian journal of ecosystem ecology (http://rjee.ru/en/) in Russian and in English.

What is the most amazing forest experience you ever had?

Unfortunately, the experience is not great. There is restoration of forests on the former agricultural lands of the «Kaluga Zaseki» Reserve, planting of oak crops in experimental forestries, preparation of forestry manuals …

_

What is your hope for Russia’s forest landscapes in 200 years?

NOW, NOTHING YET! OUR FORESTS NEED HELP!

_

What is the first thing you need help with?

- Stop logging.

- Protection of forests from fires.

- Education and training of each person. Knowledge of forest life should be by all people from childhood. Only an educated society can stop the destruction of ecosystems and move on to building and helping Nature!

_

Interview preparation: Anna Geras’kina